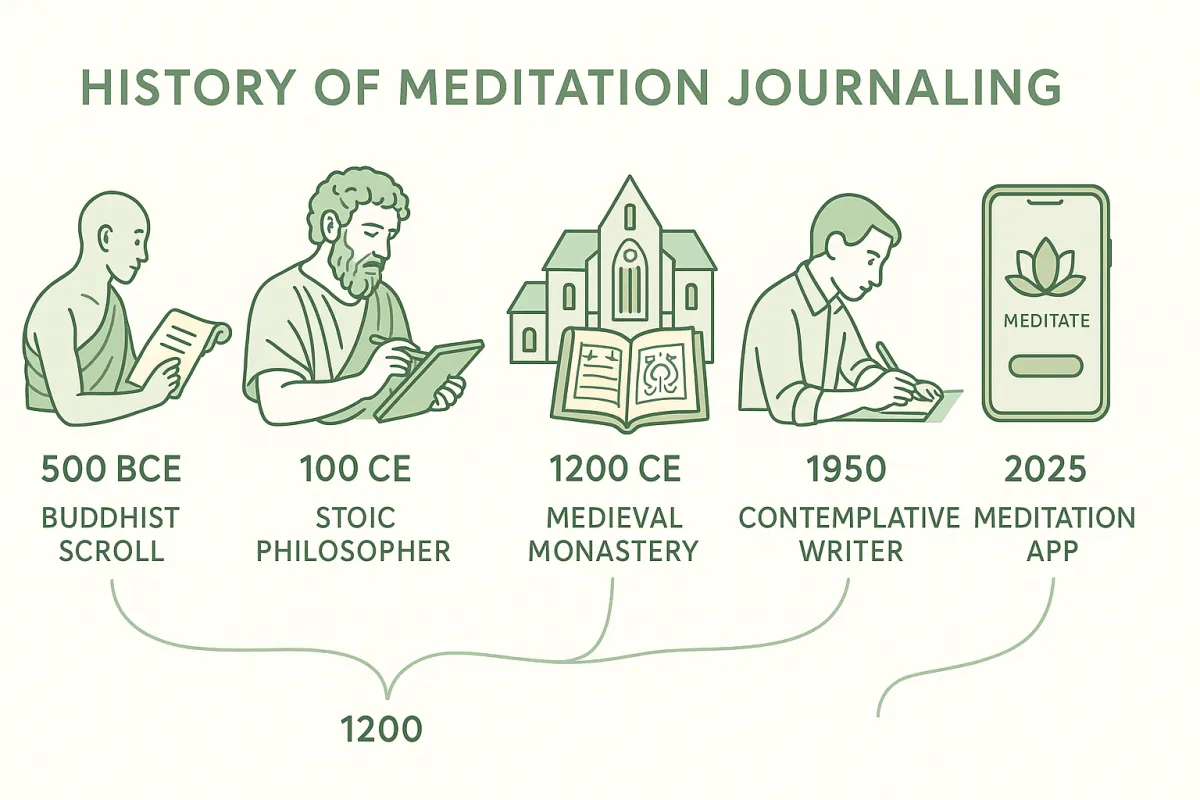

Meditation journaling isn’t a modern app feature—it’s a 2,500-year-old contemplative practice. When you write after meditation, you’re participating in the same tradition that shaped Buddhist monasteries, guided Stoic emperors, and transformed Christian mystics.

You open your meditation app, finish a 20-minute session, and see a prompt: “How was your practice today?” You think Silicon Valley invented this. Here’s what you’re actually doing: continuing an unbroken tradition that spans every major contemplative practice in human history.

We didn’t invent meditation journaling. We just forgot how ancient it is.

The Roots of Contemplative Writing (500 BCE - 500 CE)

Buddhist Sutra Reflection and Commentary

The earliest Buddhist practitioners didn’t have apps. They had something better: the discipline of written reflection.

In the Theravada tradition, monks kept gammatthana notes—structured contemplations on meditation objects. These weren’t diaries. They were technical documents tracking subtle mental states during practice.

A monk might note: “During anapanasati (breath meditation), the mind settled at the nose-tip. After 45 breaths, thoughts of the morning meal arose. Returned to breath.”

This level of specificity wasn’t navel-gazing. It was precision training for the mind.

The Tibetan tradition took this further. Advanced practitioners kept detailed records of their experiences during retreat—tracking states of concentration, insights that arose, obstacles encountered, and methods that worked.

Why write it down? Because the mind lies about its own experience.

You finish a meditation session thinking “that was terrible, my mind wandered the whole time.” But your journal from last week shows you had the exact same thought—and noted three moments of genuine stillness anyway.

The ancient wisdom: Your memory of meditation is not the same as the actual experience. Writing bridges that gap.

Stoic Journaling: Marcus Aurelius and Daily Reflection

Around 170 CE, the most powerful man in the world sat down each evening and wrote to himself.

Marcus Aurelius wasn’t keeping a diary for posterity. His Meditations were private notes—a practice he called “ta eis heauton” (things to one’s self).

Here’s what he actually wrote:

“When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil.”

This wasn’t morning affirmations. This was contemplative writing after contemplative practice.

The Stoics had a specific structure. Morning meditation (praemeditatio) to prepare for the day. Evening reflection (examen) to process what happened. Both required writing.

Seneca described it in a letter to his student Lucilius:

“The spirit ought to be examined every day. It was the custom of Sextius, when the day was over and he had retired to his evening rest, to put this question to his soul: ‘What bad habit have you cured today? What fault have you resisted? In what respect are you better?’”

Notice the pattern: silence first, then writing.

The contemplation happens in stillness. The integration happens through words.

Early Christian Desert Fathers and Written Contemplation

While Marcus Aurelius ruled Rome, Christian ascetics were walking into the Egyptian desert to sit in caves and pray.

They also wrote everything down.

The Philokalia (compiled around 300 CE) contains hundreds of written reflections from desert monastics. These weren’t theological treatises. They were field notes from inner experience.

Evagrius Ponticus, a 4th-century monk, kept detailed records of his prayer practice. He identified specific types of distracting thoughts (logismoi) and wrote precise instructions for handling each one.

When thoughts of food arose during prayer: “Remember you’ll eat later. Return to the Jesus Prayer.”

When thoughts of past conversations arose: “These words are dead. This moment is alive. Return to the prayer.”

His writings became instruction manuals because they were practical, not philosophical.

The Desert Fathers discovered what modern neuroscience would confirm 1,600 years later: writing after contemplative practice deepens the neural encoding of insights.

Medieval Monasteries and the Commonplace Book (500-1500 CE)

Lectio Divina: Sacred Reading and Response

By the medieval period, contemplative writing had become formalized in monastic rules.

The practice of lectio divina (sacred reading) had four steps:

- Lectio (read a short passage)

- Meditatio (contemplate its meaning)

- Oratio (pray in response)

- Contemplatio (rest in silence)

Then—and this is the part modern practitioners forget—there was often a fifth step: operatio (work/action).

That action was usually writing.

Monks kept commonplace books where they copied meaningful passages, then added their own reflections. These weren’t just notes. They were dialogues between text and experience.

A 12th-century monk might copy: “Be still and know that I am God.”

Then add beneath it: “This morning during Lauds, true stillness came for perhaps ten breaths. The knowing was not in words but in silence behind words. Mind keeps trying to grasp it again. Perhaps that grasping is the opposite of knowing.”

This is meditation journaling. In 1150 CE.

Monastic Rules and Daily Examination

St. Benedict’s Rule (written around 530 CE) required monks to conduct a daily examen—a structured reflection on the day’s experiences.

This wasn’t guilt-focused. It was pattern recognition.

The examining questions were precise:

- When was I most present to God today?

- When was I least present?

- What pulled me away from contemplation?

- What drew me deeper?

Monks wrote brief answers to these questions every evening. Over months and years, patterns emerged that revealed the hidden structure of their practice.

“I notice that when I sleep less than six hours, my meditation becomes agitated. When I speak too much at community meals, I struggle to return to silence.”

The ancient wisdom: You can’t spot patterns without records. Your memory is too unreliable.

The Spiritual Diary Tradition

By the late medieval period, laypeople began adopting monastic contemplative practices—including journaling.

The Book of Margery Kempe (circa 1430) is one of the earliest spiritual autobiographies in English. Kempe documented her mystical experiences and contemplative practices in extraordinary detail.

This wasn’t a literary project. It was spiritual technology.

When she wrote about her contemplative experiences, she discovered she could access them more reliably. The writing wasn’t just recording—it was training the mind to notice subtle states.

This tradition continued through the Protestant Reformation. Puritans kept detailed spiritual diaries. Quakers maintained journals of their silent meetings.

All of them discovered the same thing: Writing after silence changes both the silence and the writing.

Modern Contemplative Journaling (1900-2000)

Thomas Merton and the Contemplative Writer

In 1941, a young man named Thomas Merton entered a Trappist monastery in Kentucky and took a vow of silence.

Then he wrote. A lot.

Merton’s journals span seven volumes and thousands of pages. But they weren’t breaking his vow of silence—they were extending his contemplative practice into written form.

Here’s what he wrote in 1947:

“The silence of the forest is my bride and the sweet dark warmth of the whole world is my love. Out of the heart of that dark warmth comes the secret that is heard only in silence.”

This wasn’t poetry for publication (though he later published some of it). This was active reflection after hours of silent prayer.

Merton discovered something the Buddhist monks knew 2,000 years earlier: the insights that arise in meditation only become actionable when you write them down.

He tracked patterns in his prayer life. He noticed what helped him go deeper. He documented obstacles and breakthroughs.

A typical entry: “This morning during meditation, fifteen minutes of genuine quiet before the mind started its commentary. Note: this happened after physical work yesterday. Connection?”

That’s not mystical poetry. That’s practical meditation science.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s Mindfulness Journals

When Thich Nhat Hanh brought Zen Buddhism to the West in the 1960s, he brought the ancient practice of meditation journaling with him.

But he made one crucial adaptation.

Traditional Buddhist meditation notes were often technical and dry. Thich Nhat Hanh encouraged students to write with poetic attention to present-moment experience.

He’d give his students prompts: “Describe one breath from this morning’s meditation as if you were describing it to someone who had never breathed.”

Students wrote things like: “The air was cool entering my nostrils. I felt it more on the left side. It paused at the bottom—not a held breath, just a natural pause, like a rest in music. Then the warm air flowed out, warmer than it went in.”

This level of detail trained perception. Students who wrote this way after meditation started noticing these details during meditation.

The journaling wasn’t separate from practice. It was part of the practice.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s students kept notebooks that mixed meditation reflections, poetry, observations from daily life, and insights from his talks. These became personal contemplative documents.

Jack Kornfield and Western Buddhist Journaling

Jack Kornfield, trained in Thai and Burmese monasteries, brought another dimension to meditation journaling in the West: psychological integration.

He noticed that Western students often had profound meditation experiences that didn’t translate into daily life. They’d have insights on the cushion that vanished by breakfast.

His solution: structured post-meditation journaling. This approach, which meditation teachers across traditions now consistently recommend, creates a bridge between contemplative experience and psychological transformation.

He taught students to ask specific questions after meditation:

- What did I learn about my mind today?

- What pattern showed up again?

- What would change if I took this insight seriously?

- What’s the smallest action I could take based on what arose?

This wasn’t just reflection. It was closing the gap between insight and action.

A student might write: “During meditation, noticed how the mind creates urgency around non-urgent things. Felt the physical sensation of that urgency—tight chest, shallow breathing. What would change if I took this seriously? I’d wait 30 seconds before responding to any ‘urgent’ email.”

That last sentence—the “smallest action”—was the bridge between ancient contemplative practice and modern life.

The Digital Transformation (2000-2025)

From Paper to Pixels: Early Meditation Apps

When Headspace launched in 2010, it brought meditation to millions of people who would never have found a monastery or meditation center.

But something got lost in translation.

Early meditation apps focused on guided sessions. You’d listen to a voice, follow instructions, then the app would ping you tomorrow to do it again.

There was no journaling. No reflection. No space to integrate.

The ancient pattern—silence first, then writing—was broken.

A few apps added basic journaling features. “How do you feel? 😊 😐 😟” You’d tap an emoji, maybe add a tag, and move on.

This wasn’t contemplative writing. This was data collection.

The apps measured your meditation streak. They didn’t help you understand your mind. As neuroscience would later confirm, the critical post-meditation window for consolidating insights was being completely ignored.

Why Journaling Features Failed in First-Gen Apps

Here’s what happened: developers treated journaling as a feature instead of as part of the practice.

Traditional meditation apps had this flow:

- Open app

- Choose a session

- Meditate

- Session ends

- Close app

If journaling existed at all, it was tucked in a separate tab. An afterthought.

But ancient practitioners knew: the reflection has to be immediate. Not later. Not when you remember. Right after the silence ends. This is why meditation journals serve a fundamentally different purpose than regular journals—they capture practice-specific context while the experience is still fresh.

There’s a neurological reason for this.

The insights and experiences from meditation exist in a specific brain state. Within minutes of finishing, you’re back in your default mental mode. The insights don’t translate.

Writing immediately bridges the gap. It captures the experience while you’re still in the afterglow of practice.

First-gen apps broke this timing. So people didn’t journal. Then the apps concluded “users don’t want journaling” and removed the feature.

What actually happened: Users wanted integrated journaling. They didn’t want a separate feature they had to remember to use.

Integrated Journaling: The Next Evolution

The newest generation of meditation apps is rediscovering ancient wisdom.

Modern meditation journals now integrate reflection directly into the practice flow:

- Set your meditation timer

- Sit in silence

- Timer ends with a gentle sound

- Immediately prompted: “What do you notice?”

The journaling isn’t separate from meditation. It’s the final step of meditation.

This mirrors what Buddhist monks did with gammatthana notes. What Stoics did with evening reflection. What medieval monks did with their commonplace books.

The technology changed. The wisdom didn’t.

Some apps are going further. They’re using AI to analyze journal entries over time and surface patterns you might miss.

“You’ve mentioned ‘restlessness’ in five of your last seven sessions. All after meetings with your manager. Notice that?”

This is ancient pattern-recognition technology enhanced by modern computing.

The AI isn’t doing the contemplation for you. It’s doing what a wise meditation teacher would do: pointing out patterns so you can investigate them yourself.

What Ancient Practices Teach Modern Meditators

Immediate Reflection vs. Delayed Contemplation

Here’s what 2,500 years of practice teaches: timing matters.

Ancient practitioners distinguished between two types of written reflection:

Immediate reflection (written right after meditation):

- Captures raw experience

- Records insights while fresh

- Notes physical/mental states

- Quick, unedited, direct

Delayed contemplation (written hours or days later):

- Identifies patterns across sessions

- Makes meaning from experiences

- Connects insights to life

- Slower, more analytical

Both are valuable. But you need the immediate reflection first.

Marcus Aurelius did both. Quick notes after his morning contemplation. Longer reflections in the evening.

Buddhist monks kept daily practice notes (immediate) and monthly summary reflections (delayed).

Modern practitioners often skip the immediate step. They try to reflect on their meditation days later and wonder why they can’t remember what happened.

The ancient wisdom: Capture experience immediately. Make meaning later.

Structure vs. Freeform: Finding Your Approach

Different traditions took different approaches to contemplative writing:

Structured approaches:

- Stoic daily questions (What did you resist? What improved?)

- Ignatian examen (When did I feel most alive? Least alive?)

- Buddhist progress markers (Did concentration deepen? Did awareness expand?)

Freeform approaches:

- Stream-of-consciousness writing after sitting

- Poetic description of experience

- Whatever wants to be written

Neither is better. They serve different purposes.

Structure helps when you’re learning to notice patterns. The questions direct your attention to specific aspects of experience.

Freeform helps when you need to discover what you don’t know you’re noticing. The writing reveals insights you didn’t know you had.

Most experienced practitioners use both. Structure for daily practice. Freeform when something significant emerges.

The ancient wisdom: Use structure to build the skill. Use freeform to discover what the structure misses.

The Enduring Wisdom of Writing After Silence

Every contemplative tradition discovered the same thing:

Silence alone is not enough.

You can sit in meditation for 20 years and still not understand your mind. The insights arise in silence, but understanding comes through reflection.

Writing after meditation does three things:

- Makes experience concrete - Vague feelings become specific observations

- Creates continuity - Today’s session connects to last week’s pattern

- Enables growth - You can’t improve what you don’t track

The Desert Fathers knew this. The medieval monks knew this. Modern neuroscience confirms it.

Writing doesn’t diminish meditation. It completes it.

How to Apply Ancient Wisdom to Your Practice Today

You don’t need to join a monastery to practice 2,500-year-old contemplative wisdom.

Here’s how to integrate ancient meditation journaling into modern practice:

Right after meditation (1-2 minutes):

- What did you notice about your mind today?

- What physical sensations were present?

- Did anything surprise you?

Write quickly. Don’t edit. This captures the immediate experience.

Weekly review (5-10 minutes):

- Read your week’s entries

- What patterns emerge?

- What’s changing over time?

- What questions are arising?

This delayed contemplation reveals what individual sessions can’t show.

The tools don’t matter. Marcus Aurelius used parchment. Medieval monks used bound commonplace books. You can use a meditation journal app, a notebook, or the notes app on your phone.

What matters is the practice: Silence first, then writing. Immediate capture, then pattern recognition.

If you want to go deeper, try these ancient techniques:

From the Stoics: Ask yourself the same three questions after every session for a month. Notice what changes in your answers.

From Buddhist tradition: Keep technical notes on one aspect of your practice (breath awareness, thought patterns, emotional states). Track it systematically.

From Christian contemplatives: Write about moments when you felt most present during meditation. Over time, you’ll discover what conditions create presence for you.

From modern teachers: End each journal entry with “What’s the smallest action this insight suggests?” Then take that action before your next meditation.

The ancient practices weren’t preserved because they were old. They were preserved because they worked.

You’re not using a meditation app’s journaling feature.

You’re participating in an unbroken contemplative tradition that spans Buddhist monasteries, Roman emperor’s private writings, desert mystics’ caves, medieval commonplace books, and modern digital practice.

The technology changed. The wisdom didn’t.

Sit in silence. Then write what you notice.

That’s what contemplatives have done for 2,500 years.

That’s what will deepen your practice today.